Hike to Lone Eagle Peak in Indian Peaks Wilderness

- Dan Wagner

- Feb 22, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 9, 2024

Undoubtedly among Colorado's best day hikes, the trek to Mirror and Monarch Lakes is nothing short of remarkable. Winding through thick spruce and pines forests, weaving through stunning wildflower fields, alongside cascading waterfalls, and beneath towering peaks, the trail leads at Crater Lake, offering sweeping panoramas of one of the most iconic peaks in all of Colorado, Lone Eagle Peak.

Trailhead elevation 8,346'

Water throughout

Don't miss the view of Lone Eagle Peak from Mirror Lake

Logistical Considerations of Hiking to Lone Eagle Peak

There are two routes that lead to Lone Eagle Peak, both of which can be done as a long day hike or overnight backpack. The first option is a 19-mile round trip hike via Pawnee Pass from the Brainard Lake Recreation Area. Depending on the time of year, this option may require day hikers to purchase a day use parking permit for either the Brainard Lake Trailhead or Long Lake Trailhead. Backpackers starting the trek from Pawnee Pass may be required to purchase both an Overnight Parking Permit for Brainard Lake and an Indian Peaks Wilderness Overnight Permit. Permits are highly competitive and can be purchased on recreation.gov.

The second option covers 16 miles beginning from the Monarch Lake Trailhead, located 15 miles east of Granby, Colorado. Day hikers are required to purchase either an Arapaho National Recreation Area day pass from recreation.gov or use their America the Beautiful pass to park at the trailhead. Backpackers are required to do the same, as well as purchase an Indian Peaks Wilderness Overnight Permit.

Backpacking either route requires hikers to adhere to the designated camping zones, which includes established campsites along Mirror Lake and Crater Lake.

Hike to Lone Eagle Peak from Monarch Lake

The hike to Lone Eagle Peak from the Monarch Lake Trailhead is an extremely popular option, and as such, the parking area tends to fill quickly, especially on weekends. That being said, an early arrival is highly recommended. From the trailhead, the route initially traces along the northern edge of Monarch Lake for approximately one mile, maintaining a level terrain throughout.

Once leaving the lake behind, the trail curves to the left and winds through a marshy landscape, where it's not uncommon to observe moose grazing leisurely amidst the grass during the morning hours. Around the 1.6-mile mark, the trail reaches a well-marked junction with the Arapaho Pass Trail. Here, hikers proceed to the left, following the Cascade Creek Trail, which signals the beginning of the trek through Hell Hole Canyon.

Today, Hell Hole Canyon is a sprawling paradise. However, nearly a century prior to a hiking trail being constructed through it, it stood as an unrelenting canyon. In the mid-1800s, a party of pioneer railroad engineers found themselves ensnared in the canyon's unforgiving terrain. After losing their way for several days, they managed to correct course and upon exiting, christened the canyon with the ominous name "Hell Hole Canyon."

Over the next two miles, the trail parallels Buchanan Creek, steadily ascending while intermittently providing glimpses of Cascade Creek beneath thick stands of pine trees. At approximately 3.5 miles into the hike, the trail reaches a clearly marked junction with the Buchanan Pass Trail. Shortly thereafter, within a quarter-mile, the path meanders beside the first of four waterfalls along the Cascade Creek Trail.

After passing the waterfall, the trail diverges from Buchanan Creek and transitions to Cascade Creek. One mile ahead, it arrives at Cascade Falls, a picturesque multi-drop waterfall positioned to the left of the trail. This area becomes particularly eye-catching during wildflower season, featuring vibrant displays of marsh marigold and Colorado Columbine, among others.

Following Cascade Falls, the trail ascends more steeply, eventually leading to a more open view of Hell Hole Canyon. Here, as hikers progress toward the Continental Divide, they will find views of Cherokee Peak in the distance to their right, while Mount Toll and Pawnee Peak loom ahead.

Around the 6.5-mile mark, the trail arrives at a well-marked junction with the Pawnee Pass Trail, just before encountering the first of two unbridged creek crossings. Depending on water levels, these crossings may vary from simple rock hopping to reaching calf depth. The trail can be slightly challenging to locate between the two crossings and hikers should be aware that this area is often frequented by moose, elk, and black bears.

Following the second creek crossing, the trail steeply ascends through a dense forested area, often obstructed by fallen trees. Upon reaching a large granite outcropping, the trail arrives at the eastern edge of Mirror Lake. Here, along the lake's rear, hikers are treated to unparalleled views of Lone Eagle Peak, its imposing granite facade looming in the distance. Hopi Peak, Iroquois Peak, Mount Achonee, and Cherokee Peak lie to the west of Lone Eagle Peak, while to the east stands Apache Peak. Together, they form the Lone Eagle Cirque.

Moving on, the trail then leaves Mirror Lake and proceeds towards the pine fringed shoreline of Crater Lake. At 10,331 feet, the emerald hued pool marks the high point of the hike. Massive granite boulders surround the lake's perimeter, offering an endless supply of spots for hikers to relax and take in the stunning views from.

Fair and Peck Glaciers flank Lone Eagle Peak from opposite directions. Fair Glacier, named after Fred Fair who discovered it in 1904, is tucked behind the eastern slope of the peak and remains hidden from view. It feeds Triangle Lake below, the wellspring of Cascade Creek, the predominant watercourse traced along the majority of the hike. Conversely, Peck Glacier rests on the western slope of Lone Eagle Peak and is readily visible from Crater Lake.

A lengthy knife-edge ridge runs southward from Lone Eagle Peak, connecting it to the imposing Iroquois Peak rising in the background. Hikers can catch glimpses of the ridge as they move along the western edge of Crater Lake. After exploring the area, hikers can retrace their steps back to the trailhead.

History of Lone Eagle Peak

Prior to 1927, the imposing granite pinnacle known today as Lone Eagle Peak lacked a designation. However, on August 31st of that year, a mere two and a half months after Charles Lindbergh's historic solo transatlantic flight from New York to Paris, Fred Fair, renowned for discovering the Fair and Isabelle Glaciers, proposed christening the peak in tribute to Lindbergh.

Professor Russell George of the University of Colorado's Geological Department described the locale as follows: "Situated near the mighty Arapaho Peak, the the heart of the glacial area, this gorge wears its apron of snow most of the year. The lone peak at its mouth, sentinel-like, is in my opinion, an added incentive for choosing this place. It would make a happy choice for "Lindbergh gorge and peak." Shortly after, George put his stamp of approval on Fair's proposal and the peak became known as Lindberg Peak.

Years later, after learning that naming a mountain peak after a living person was taboo, Lindbergh Peak was renamed Lone Eagle Peak, paying homage to one of Lindbergh's monikers, "The Lone Eagle."

The first recorded summit of Lindbergh Peak was accomplished on Labor Day 1929, by three Denver men, namely Carl Blaurock, Stephen Hart, and William Ervin. After two failed attempts at reaching the summit from the west, the three men reached the top of the peak from the east using ice axes and rope.

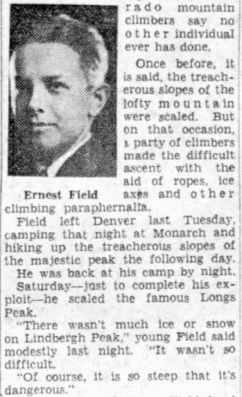

Less than a year later, on July 23, 1930, the first unassisted summit of Lindbergh Peak was accomplished, remarkably by 16-year-old Denver native Ernest Field.

Five years following Field's first unassisted summit, tragedy befell Lone Eagle Peak in August 1935, claiming the life of 15-year-old William Brode. While participating in a YMCA summer camp expedition, Brode diverged from his peers, opting to linger by the tranquil waters of Monarch Lake as they embarked on a supervised mountain climb. Subjected to ridicule for his decision to remain behind, Brode, accompanied by a companion, ventured towards the daunting heights of the peak. As recounted by his climbing companion, Brode's attention was lost by the ominous echoes of tumbling rocks, leading to his fatal fall from the knife-edge ridge. Following an exhaustive search spanning more than 50 grueling hours, Brode's lifeless body was discovered buried within a 100-foot deep crevice and lowered down from the mountain.

_edited.png)